Object-Capability SQL Sandboxing for LLM Agents

$1K CTF Bounty to Break It

The Problem: Agents Need SQL, SQL Is Dangerous

The killer app for LLM agents is database access: querying, updating, acting on real data. But the standard pattern — execute_sql(<string>) — is a security disaster. One prompt injection and an agent leaks PII, drops tables, or exfiltrates your entire database.

System prompts don’t fix this. They’re guardrails made of tape. A sufficiently creative injection bypasses them because the agent still can express any SQL query. The attack surface is the full SQL language.

The real question: can you give agents useful database access while making dangerous queries inexpressible?

The Approach: Object-Capability Constraints

The answer borrows from object-capability security: don’t try to detect bad queries — make them impossible to construct.

Here’s how it works:

- The agent writes JS inside a sandbox (Deno, Cloudflare Workers, etc.) with capability transport via Cap’n Web

- Its only database access is through a query builder that enforces data boundaries at the AST level

- Row, column, and relation constraints are baked into the capability grants — not bolted on as runtime checks

The agent never touches SQL strings. It composes queries through typed objects that cannot express unauthorized access.

Defining Capabilities

Capabilities are defined as classes. Each class gates what the agent can reach:

class User extends db.Table('users').as('user') {

id = this.column('id')

name = this.column('name')

@tool()

posts() {

// Agent can ONLY access posts owned by this user instance

return Post.on(post => post.userId['='](this.id)).from()

}

}The @tool() decorator exposes posts() to the agent. The relation constraint — post.userId = this.id — is structural. The agent can’t remove it, override it, or work around it because it’s part of the object it received, not a filter it controls.

Composing Queries

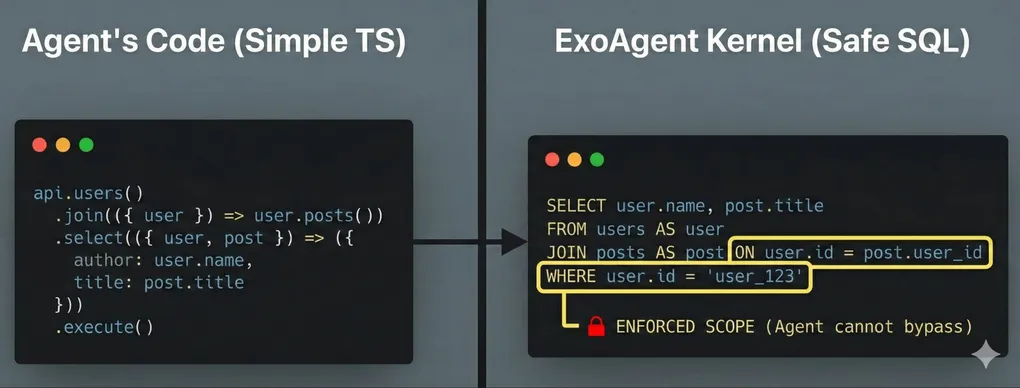

The agent composes queries within those constraints:

api.users()

.join(({ user }) => user.posts())

.select(({ user, post }) => ({ author: user.name, title: post.title }))

.execute()This compiles to:

SELECT user.name AS author, post.title AS title

FROM users AS user

JOIN posts AS post

ON user.id = post.user_id -- enforced by capability

WHERE user.id = '...' -- enforced by capabilityThe ON and WHERE clauses aren’t added by the agent. They’re injected by the capability layer during SQL compilation. The agent cannot express a query that accesses another user’s posts because no API surface exists to do so.

Why This Works

Traditional SQL security relies on blacklists: block known-bad patterns. Object-capabilities invert this to a whitelist: only expressible queries are allowed, and expressibility is defined by the capability graph.

An agent that receives a User object scoped to user abc-123 literally cannot:

- Query other users’ data (no API to change the scope)

- Access tables not reachable from its capability grants (no reference to them)

- Inject raw SQL (no string concatenation path exists)

The attack surface shrinks from “the entire SQL language” to “the set of queries expressible through granted capabilities.”

Limitations & Comparisons

Why not Postgres RLS? Two reasons:

- (a) Defense in depth. RLS has existed for a decade, yet no security team allows raw, untrusted SQL to run against production databases. You still need protection against resource exhaustion, unsafe functions, and column-level leaks.

- (b) Logic beyond the DB. RLS is locked to the database. The vision is to build a general-purpose policy layer that enforces rules spanning systems, like: “The email column is PII. PII cannot be sent to the Slack tool.”

What about parameterized queries? Parameterized queries prevent SQL injection. They don’t prevent authorized overfetch — a different threat model entirely.

What doesn’t this cover? This approach is scoped to SQL. It doesn’t address DoS, and it can’t stop an agent from making a bad decision within its grants (e.g., using data it legitimately has access to but drawing the wrong conclusion).

CTF: Prove Me Wrong

Theory is cheap. So here’s a live challenge: two agents, same schema, both guarding a bitcoin wallet.

- Agent A: Protected by a system prompt. Break it, take the BTC.

- Agent B: Protected by the capability layer. Break it, take the BTC (~$1K).

Agent A exists to calibrate difficulty. If you can break the system prompt but not the capability layer, that’s the point.

- Repo: github.com/ryanrasti/exoagent

- Challenge: exoagent.io/challenge

The code is open source. Read the implementation, find a flaw, claim the bounty.

Update (Jan 29): Agent A (system prompt only) was bypassed within minutes. Agent B remains unbroken.

Built as part of Exoagent. Feedback and PRs welcome.